Files, Directories and Merkle Trees 🌲

When you create a commit within Oxen, you can think of it as a snapshot of the state of the files and directories in the repository at a particular point in time. This means each commit will need a reference to all the files and directories that are present in the repository at that point in time.

Let's use a small dataset as an example.

README.md

LICENSE

images/

image0.jpg

image1.jpg

image2.jpg

image3.jpg

image4.jpg

This is a simple file structure with a README.md at the top level and a sub-directory of images. Start by initializing a new repository, then adding and committing the files.

oxen init

oxen add README.md

oxen add images/

oxen commit -m "adding data"

On commit we save off all the hashes of the file contents and save the data into a Content Addressable File System (CAFS) within the .oxen/versions directory. This makes it so we don't duplicate the same file data across commits.

$ tree .oxen/versions/

.oxen/versions/

├── 43

│ └── 94f02b679bcf0114b1fb631c250d0a

│ └── data

├── 58

│ └── 8b7f5296c1a6041d350d1f6be41b3

│ └── data

├── 64

│ └── e1a1512c6d5b1b6dcf2122326370f1

│ └── data

├── 74

│ └── bfd17b6b7c9b183878a26e1e62a30e

│ └── data

├── 7c

│ └── 42afd26e73b8bfbc798288f1def1ed

│ └── data

├── c8

│ └── 2d11a1e1223598d930454eecfab6ea

│ └── data

└── dc

└── 92962a4b05f5453718783fe3fc4b10

└── data

15 directories, 7 files

Each file is accessible by its hash and original extension the file was stored with. For example, the hash of images/image0.jpg is 74bfd17b6b7c9b183878a26e1e62a30e and it's extension is jpg, so the original contents can be found at .oxen/versions/74/bfd17b6b7c9b183878a26e1e62a30e/data.

To find the hash and extension of any file in a commit, you can use the oxen info command.

oxen info images/image0.jpg

74bfd17b6b7c9b183878a26e1e62a30e 13030 image image/jpeg jpg 12099a4ca3b15c36

The CAFS makes it easy to fetch the file data for a given commit, but we need some sort of database that lists the original file names and paths. This way when switching between commits we can efficiently restore the files that have been added/changed/removed.

Switching Between Versions

The simplest solution would be to have a key-value database for every commit that listed the file paths and pointed to their hashes and extensions.

Commit A

README.md -> {"hash": "64e1a1512c6d5b1b6dcf2122326370f1", "extension": ".md"}

LICENSE -> {"hash": "7c42afd26e73b8bfbc798288f1def1ed", "extension": ""}

images/image1.jpg -> {"hash": "74bfd17b6b7c9b183878a26e1e62a30e", "extension": ".jpg"}

images/image2.jpg -> {"hash": "dc92962a4b05f5453718783fe3fc4b10", "extension": ".jpg"}

images/image3.jpg -> {"hash": "588b7f5296c1a6041d350d1f6be41b3", "extension": ".jpg"}

images/image4.jpg -> {"hash": "c82d11a1e1223598d930454eecfab6ea", "extension": ".jpg"}

images/image5.jpg -> {"hash": "4394f02b679bcf0114b1fb631c250d0a", "extension": ".jpg"}

We could store this in a rocksdb database in .oxen/history/{commit_hash}/files. The keys would be the file paths and the values would be the hashes and extensions. Then when swapping between commits all we would have to do is clear the current working directory and re-construct all the files from the respective commit database!

Psuedo Code:

set commit_hash 1d278f841510b8e7

rm -rf working_dir

for dir, hash, ext in (oxen db list .oxen/versions/files/$commit_hash/) ;

mkdir -p working_dir/$dir ;

cp .oxen/versions/files/$commit_hash/$hash/data$ext working_dir/$dir/ ;

end

Version control complete. Let's call it a day and go relax on the beach 😎 🏝️.

Of course, we are not here to build naive inefficient version control tool. Oxen is a blazing fast version control system that is designed to handle large amounts of data efficiently. Even if clearing and restoring the working directory is simple, there are many reasons it is not optimal (including wiping out untracked files).

Data Duplication 😥

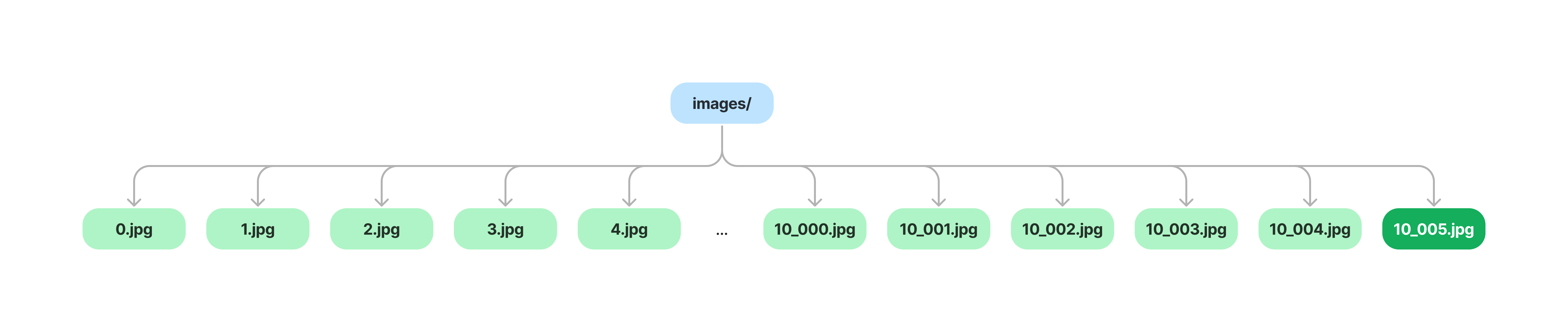

To see why this naive approach is sub-optimal, imagine we are collecting image training data for a computer vision system. We put Oxen in a loop adding one new image at a time to the images/ directory. Each time we add an image we commit the changes.

for i in (seq 100) ;

# imaginary data collection pipeline

cp /path/to/images/image$i.jpg images/image$i.jpg ;

# oxen add and commit

oxen add images/image$i.jpg ;

oxen commit -m "adding image$i" ;

end

If we had gone the naive route, this would balloon in redundancy even with just our list of pointers to hashes. Each database list repeats the same file paths and the hashes over and over again.

Commit A

README.md -> hash1

LICENSE -> hash2

images/image0.jpg -> hash3

images/image1.jpg -> hash4

images/image2.jpg -> hash5

images/image3.jpg -> hash6

Commit B

README.md -> hash1 # repeated 1 time

LICENSE -> hash2 # repeated 1 time

images/image0.jpg -> hash3 # repeated 1 time

images/image1.jpg -> hash4 # repeated 1 time

images/image2.jpg -> hash5 # repeated 1 time

images/image3.jpg -> hash6 # repeated 1 time

images/image4.jpg -> hash7 # NEW

Commit C

README.md -> hash1 # repeated 2 times

LICENSE -> hash2 # repeated 2 times

images/image0.jpg -> hash3 # repeated 2 times

images/image1.jpg -> hash4 # repeated 2 times

images/image2.jpg -> hash5 # repeated 2 times

images/image3.jpg -> hash6 # repeated 2 times

images/image4.jpg -> hash7 # repeated 1 time

images/image5.jpg -> hash8 # NEW

...

Commit 10_000

README.md -> hash1 # repeated N times

LICENSE -> hash2 # repeated N times

images/image0.jpg -> hash3 # repeated N times

images/image1.jpg -> hash4 # repeated N times

images/image2.jpg -> hash5 # repeated N times

images/image3.jpg -> hash6 # repeated N times

images/image4.jpg -> hash7 # repeated N times

images/image5.jpg -> hash8 # repeated N times

...

images/image10_000.jpg -> hash10_000

Do the math once we get to a dataset of 10,000 images. Each commit duplicates 10,000+1 values. 10,000 + 10,001 + 10,002 + 10,003 = 40,006 values in our collective databases.

.oxen/history/COMMIT_A/files -> 10,000 values

.oxen/history/COMMIT_B/files -> 10,001 values

.oxen/history/COMMIT_C/files -> 10,002 values

.oxen/history/COMMIT_D/files -> 10,003 values

Total Values: 40,006

A key observation is that we are duplicating a lot of data across commits. This will be a common pattern to look for when optimizing the storage within Oxen.

Optimizations w/ Merkle Trees

Adding one file should not require to you copy the entire key-value database. We need some sort of data structure that can efficiently store the file paths and hashes without duplicating too much data across commits.

Enter Merkle Trees 🌲.

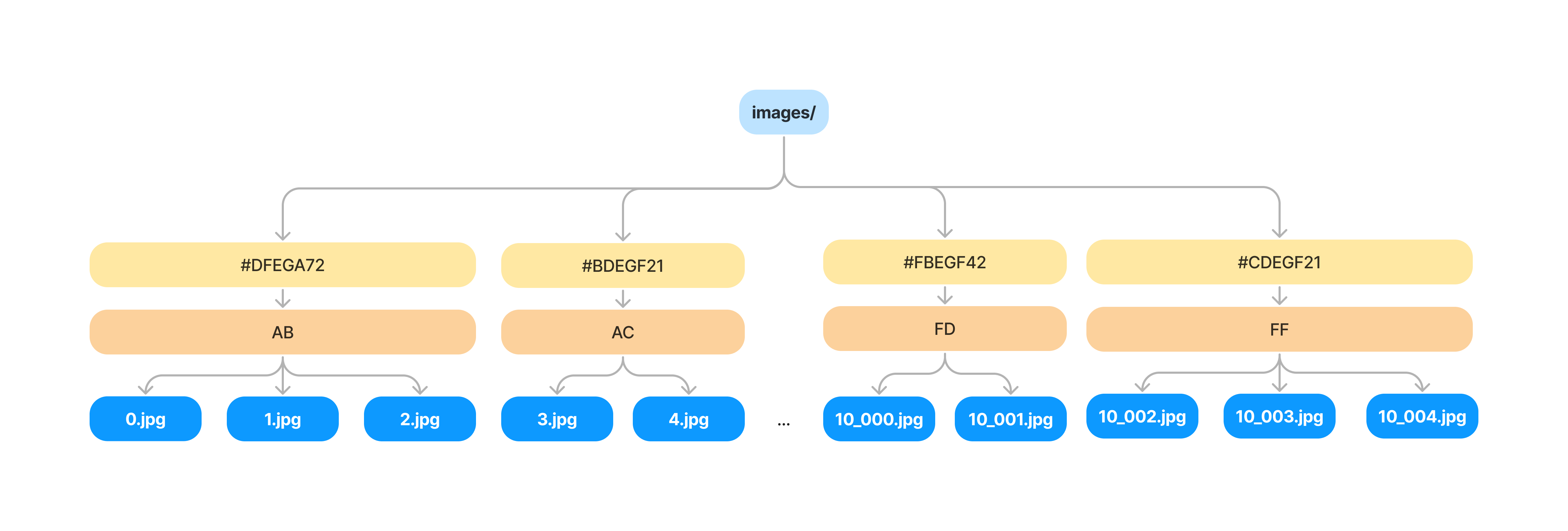

Files and directories are already organized in a tree like fashion, so a Merkle Tree is a more natural fit for storing and traversing the file structure to begin with. The Oxen Merkle Tree implementation also make it so when we add additional data, we only need to copy subtrees instead of copying the entire database for each commit.

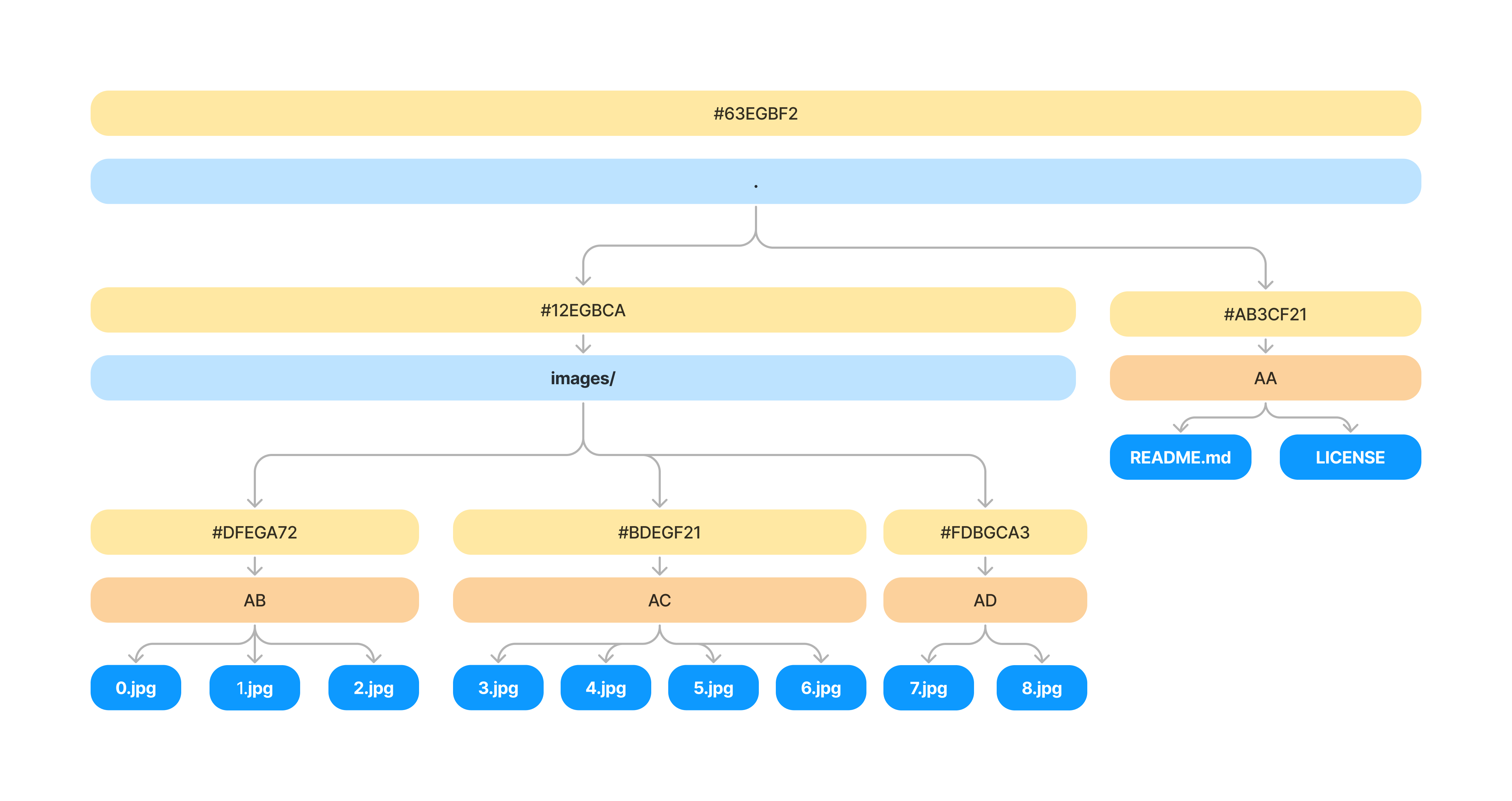

What does a Merkle Tree within Oxen look like?

At the root node of the Merkle tree is a commit hash. This is the identifier you know and love which you can reference any commit in the system by.

The root commit hash represents the content of all the data below it, including the files contained in the images/ directory as well as the files directly in the . root directory (README.md, LICENSE, etc). Additionally all the files within a directory get sectioned off into VNodes. We will return to the importance of VNodes in a bit.

At each level of the tree we see the contents of all the files hashed within that directory, and bucketed into VNodes.

Adding a File

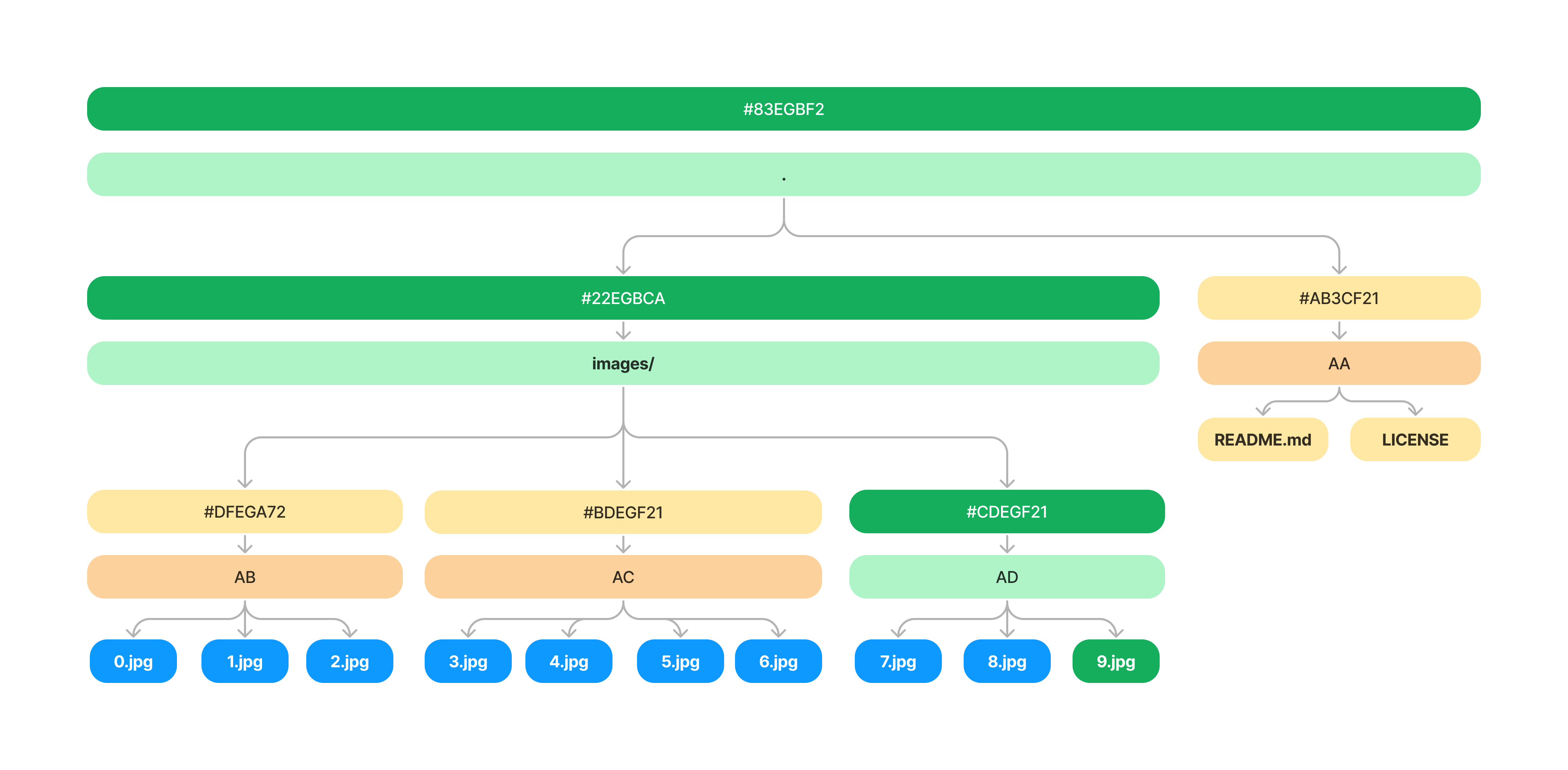

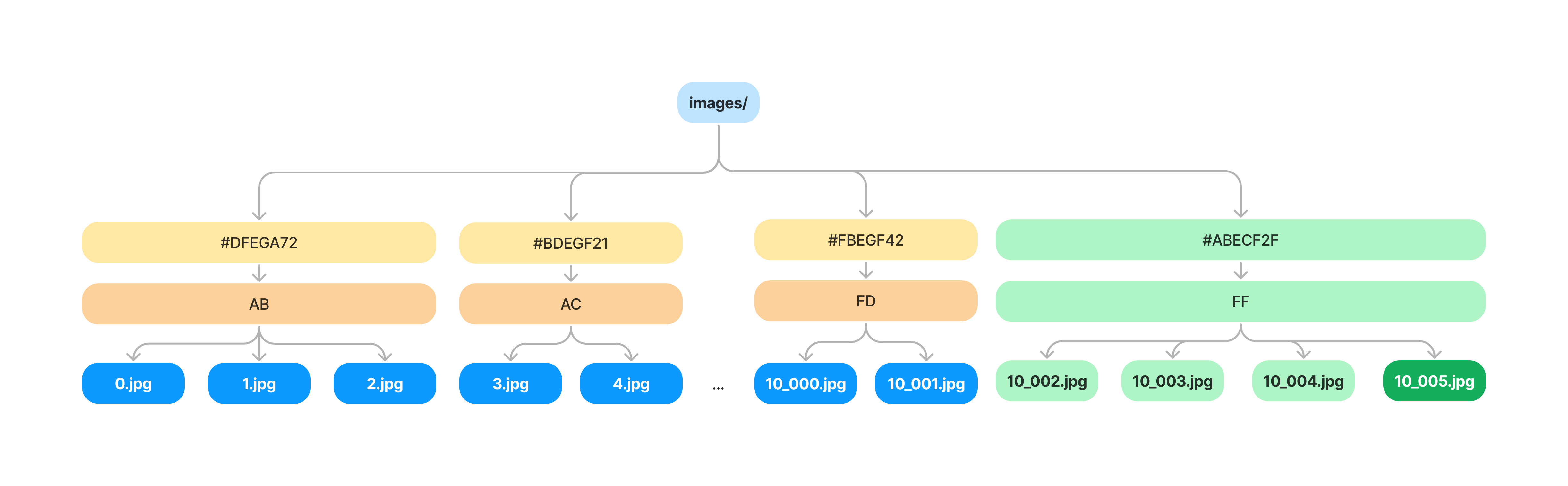

To see what happens when we add a new file to our repository, let's revisit our previous example of adding images to the images/ directory. Say we have 8 images in our images/ directory and we want to add a new image (9.jpg).

The first thing we have to do is find which VNode bucket it falls into (more on this later). Then we can recompute the hash of this subtree, and recursively update the hashes above it until we get to the root node.

In this case we make four total updates to the tree, highlighted in green.

- Add the contents of the new image to our

.oxen/versions/directory - Find the VNode it belongs to, and deep copy it to a new VNode with a new hash

- Update the VNode hash of the

images/parent directory - Update the root node hash

The Merkle Tree nodes are all global to the repository, and can get re-used and shared between commits. Instead of copying the entire database to our new commit, only copy the subtrees that changed. On adding a file, we only need to update a single VNode and copy it's contents. This is a much faster operation than copying every file within our databases.

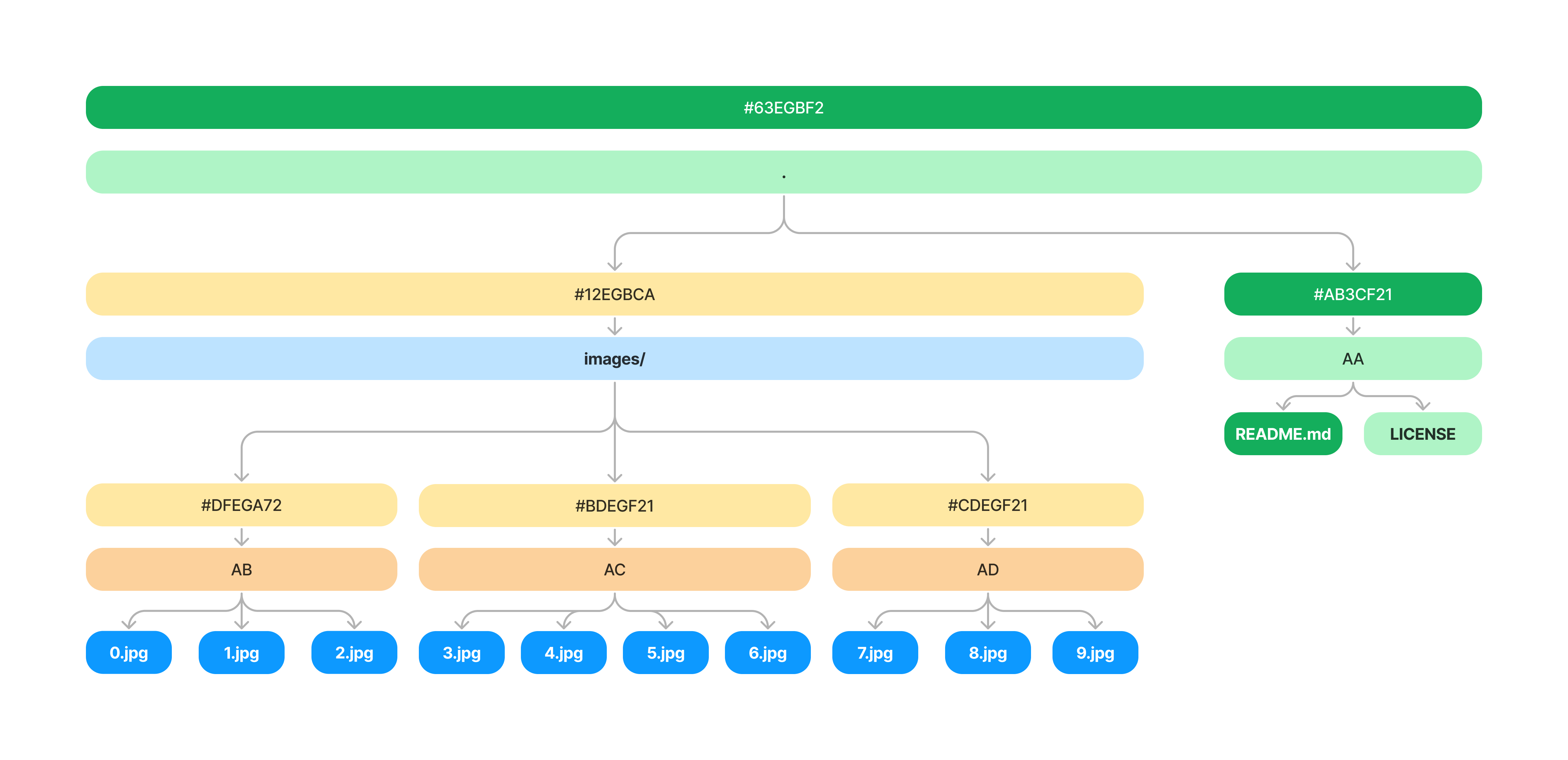

For another example, let's see what happens when we update the README.md file.

This time, we only need to update the VNode that contains the README.md file and it's parent in the root node.

Why use VNodes?

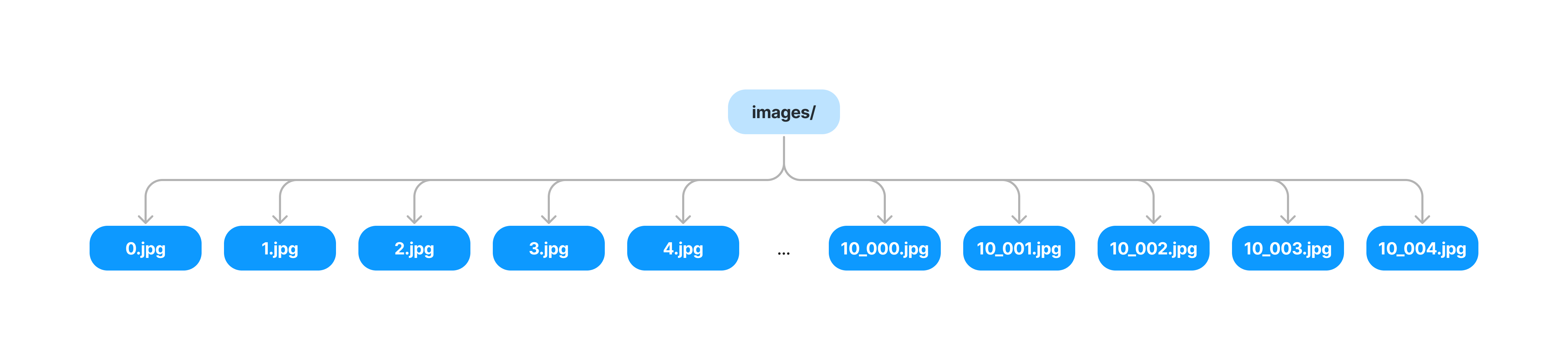

One of the goals of Oxen is to be able to scale to directories with an arbitrary number of files. Imagine for a second that you have a directory of 100k or 1 million images. Storing all of these values directly at the directory level node would be inefficient. Every time you commit a single image to the directory, you would need to copy all the pointers and recompute the hash for the entire directory.

For example imagine we had no VNodes at the directory level.

If we want to add a single file, we would have to copy all the pointers and recompute the hash for the entire directory.

VNode's add an intermediate bucket we can add files to so that we only have to copy a subset of pointers. Which VNode a file belongs to is computed from the hash of file path name itself. This way files get evenly distributed into buckets within the tree.

You'll notice two parts to the VNode. The first is first two letters (AB) of the hash of the file path name, and the second is the hash of the VNode contents (#DFEGA72). To add an image, now we only need to find the bucket (based on it's file path), compute it's new hash, and make a copy of the items of the VNode database for it's new hash.

To drive this home, let's go back to our example directory with 10,000 images with the naive implementation from before. Remember 4 additions to the images directory after it contained 10,000 node resulted in 40,006 values in our database. Say our bucket size for VNodes is 10,000/256 ~= 40. This means on average we are copying 40 values with each commit. This will result in 10,160 total values in our DB instead of 40,006.

Printing the Merkle Tree

To bring these concepts to life, let's create a repo of many images and use the oxen tree command to print the Merkle Tree. In the Oxen-AI/Oxen repo we have a script that will create a directory with an arbitrary number images and add them to the images/ directory.

When developing and testing Oxen, this script is handy to generate synthetic datasets to push the performance of the system. For example you could create a dataset of 1,000,000 images and see how long it takes to add and commit the changes.

# WARNING: This will create a directory with 1,000,000 images and take a while to run

$ python benchmark/generate_image_repo_parallel.py --output_dir ~/Data/1m_images --num_images 1000000 --num_dirs 2 --image_size 64 64

For this example we will stick to a smaller dataset of 20 images. It will be easier to visualize the Merkle Tree.

# 😌 This will create a much smaller dataset of 20 images

$ python benchmark/generate_image_repo_parallel.py --output_dir ~/Data/20_images --num_images 20 --num_dirs 1 --image_size 64 64

After the dataset is created, go ahead and create and initialize an oxen repository.

$ cd ~/Data/20_images

$ oxen init

Before we add and commit the files, we are going to make a quick tweak to the configuration to use a smaller VNode bucket size. The default size is 10,000, but we are going to set it to 5 to make it easier to see the tree updates in this toy example.

Edit the .oxen/config.toml file to set the vnode_size to 5.

$ cat .oxen/config.toml

remotes = []

min_version = "0.19.0"

vnode_size = 6

Now add and commit the files.

$ oxen add .

$ oxen commit -m "adding all data"

Then we can use the oxen tree command to print the entire Merkle Tree.

$ oxen tree

[Commit] bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd "adding data" -> Bessie ox@oxen.ai parent_ids ""

[Dir] 7a892f11ae586978f3b170182599cc5e "/" (15.8 MB) (22 files) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd) (1 children)

[VNode] 801de12b06a74b5a2d0b978af067e32b (3 children)

[File] dcd78180c335f3afed68656b6b12c248 "README.md" (98 B) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[Dir] 73ae655940b4873cf6b1557c3806d65c "images/" (15.8 MB) (20 files) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd) (1 children)

[VNode] 51d73f367fcbc4f11228ff2e56fba5d3 (1 children)

[Dir] 79c6625dcad70d16be56aca9426442ee "split_0/" (15.8 MB) (20 files) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd) (4 children)

[VNode] 3543cada59e52d3a391603661b6f9721 (6 children)

[File] 6d11185298ec825208a1f3fce23b9d6c "noise_image_14.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 56e2d45af9958af0680fceb3ab00d18c "noise_image_17.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 82c2ec408abf2defc2dd5289b29a1e80 "noise_image_19.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 1d952254a3be50f3d2d70a1398aee524 "noise_image_4.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] cb118df353e0814d42472818405b9384 "noise_image_7.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 2ccc49262256aae9802c581d90736b34 "noise_image_9.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[VNode] e5529567f3246881d58335ee5102281c (4 children)

[File] 38593fea717a1d4c2e771674ebc9ca81 "noise_image_0.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] d0871bf54a0c99f2336da66ab20b6785 "noise_image_1.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] e406e9a852da65dad3f012dd86a98919 "noise_image_10.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 48dca231fd96fd847935e7e6623b32d9 "noise_image_11.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[VNode] c9e4baf0332cf23a803a8870e295e0b5 (7 children)

[File] abf629ca6ed9414e8a4f884d2f98dd2a "noise_image_13.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 4598fdac03e5aaa52aa5cd1c51231a2 "noise_image_15.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 3e0989396c1d6a7f38164faf96c4662e "noise_image_18.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 1506f02a6a10123af68084200b67583a "noise_image_2.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 1d72a37baeef7b0c02b4ce7482e4592 "noise_image_5.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 26e656316e9e292f8b27fcb49654237a "noise_image_6.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 4f3611ebc27072c6359ac05f4e6c98e "noise_image_8.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[VNode] 38c8edc066ae7d1ac36a92223a9c39ee (3 children)

[File] 6dc552a73f1beb27356903f84c4a7b33 "noise_image_12.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 9335d768de6058fbe3da1a7857c400e7 "noise_image_16.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 4855043d603912f6141f5f148851146f "noise_image_3.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] fe0b2b028ff23fd726b14f6c7694ffd8 "images.csv" (764 B) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

The first thing you'll notice is that each VNode is not guaranteed to have 6 children. This is because we first instantiate the number of VNodes given the VNode size, and then we fill them with the files. The hashing algorithm will then distribute the files across the VNodes given the file hash % number of VNodes and some VNodes will end up with more children than others. On average a good hashing algorithm will distribute the files evenly across the VNodes.

Remember - VNodes exist in order to help us update smaller subtrees when we add, remove or change a file. To see this in action, let's add a new image to the images/split_0 directory by converting a png to jpeg.

ffmpeg -i images/split_0/noise_image_11.png images/split_0/noise_image_11.jpg

oxen add images/split_0/noise_image_11.jpg

oxen commit -m "adding images/split_0/noise_image_11.jpg"

Then print the tree again, and try to find where the new image was added.

$ oxen tree

[Commit] 1382a90346dce99134fbb8a7359d81df "adding images/split_0/noise_image_11.jpg" -> Bessie ox@oxen.ai parent_ids "bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd"

[Dir] 73aa45daae11e300cb452b072f22bc3a "/" (16.0 MB) (23 files) (commit 1382a90346dce99134fbb8a7359d81df) (1 children)

[VNode] 57e2282b08cfdb57c66d5c2c0341fc2d (3 children)

[File] dcd78180c335f3afed68656b6b12c248 "README.md" (98 B) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[Dir] 7363444d86e0cb47c4247bd7f05c13f3 "images/" (16.0 MB) (21 files) (commit 1382a90346dce99134fbb8a7359d81df) (1 children)

[VNode] 8344a2ef7c01c891fb33a357efabc2b6 (1 children)

[Dir] b5d819fd018381b3026848bed854830b "split_0/" (16.0 MB) (21 files) (commit 1382a90346dce99134fbb8a7359d81df) (4 children)

[VNode] 3543cada59e52d3a391603661b6f9721 (6 children)

[File] 6d11185298ec825208a1f3fce23b9d6c "noise_image_14.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 56e2d45af9958af0680fceb3ab00d18c "noise_image_17.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 82c2ec408abf2defc2dd5289b29a1e80 "noise_image_19.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 1d952254a3be50f3d2d70a1398aee524 "noise_image_4.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] cb118df353e0814d42472818405b9384 "noise_image_7.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 2ccc49262256aae9802c581d90736b34 "noise_image_9.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[VNode] e5529567f3246881d58335ee5102281c (4 children)

[File] 38593fea717a1d4c2e771674ebc9ca81 "noise_image_0.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] d0871bf54a0c99f2336da66ab20b6785 "noise_image_1.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] e406e9a852da65dad3f012dd86a98919 "noise_image_10.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 48dca231fd96fd847935e7e6623b32d9 "noise_image_11.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[VNode] c9e4baf0332cf23a803a8870e295e0b5 (7 children)

[File] abf629ca6ed9414e8a4f884d2f98dd2a "noise_image_13.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 4598fdac03e5aaa52aa5cd1c51231a2 "noise_image_15.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 3e0989396c1d6a7f38164faf96c4662e "noise_image_18.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 1506f02a6a10123af68084200b67583a "noise_image_2.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 1d72a37baeef7b0c02b4ce7482e4592 "noise_image_5.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 26e656316e9e292f8b27fcb49654237a "noise_image_6.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 4f3611ebc27072c6359ac05f4e6c98e "noise_image_8.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[VNode] 88e4003b65f2f3f16c16a91230593746 (4 children)

[File] 6550c5d7deaa62dbb78d8effbbda375f "noise_image_11.jpg" (285.4 KB) (commit 1382a90346dce99134fbb8a7359d81df)

[File] 6dc552a73f1beb27356903f84c4a7b33 "noise_image_12.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 9335d768de6058fbe3da1a7857c400e7 "noise_image_16.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] 4855043d603912f6141f5f148851146f "noise_image_3.png" (788.1 KB) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

[File] fe0b2b028ff23fd726b14f6c7694ffd8 "images.csv" (764 B) (commit bb2e7778ddc8f40788d4d34993955bfd)

You will see that the vnode 88e4003b65f2f3f16c16a91230593746 is the one that contains the new image. The other VNode's have not changed. As a result, we only had to make a copy of a single node with 3 children instead of 20.

When you get into larger directories, there is a trade off between number of vnodes and the size of the vnode. The fewer number of vnodes, the faster it will be to read all the nodes. The smaller the vnode, the faster it will be to write, and less data we copy when we add, remove or change a file. In practice we find 10k entries per vnode is a good compromise in terms of storage and performance.

File Chunk Deduplication

Not yet implemented, but scoped out here:

Benefits of the Merkle Tree

Hopefully if you are new to Merkle Trees, this should give you a good intuition for how they work in practice. There are a few nice properties of a Merkle Tree as our data structure.

-

When we add, remove or change a file, we only need to update the subtree that contains that file. This means the storage grows logarithmically with the number of files in the repository instead of linearly.

-

To recompute the root hash of a commit, we only need to hash the file paths and the hashes of the files that have changed. This means we can efficiently verify the integrity of the data by recomputing subtrees instead of the whole tree.

-

We can use it to understand the small chunks of the data that changes when transferring over the network when syncing repositories.

-

Since each subtree is also a merkle tree, this will allow us to clone small subtrees, make changes, and push them back up to the parent. This can be powerful when you only want to update the README for example but have a directory of images you are not planning on changing.