Repositories

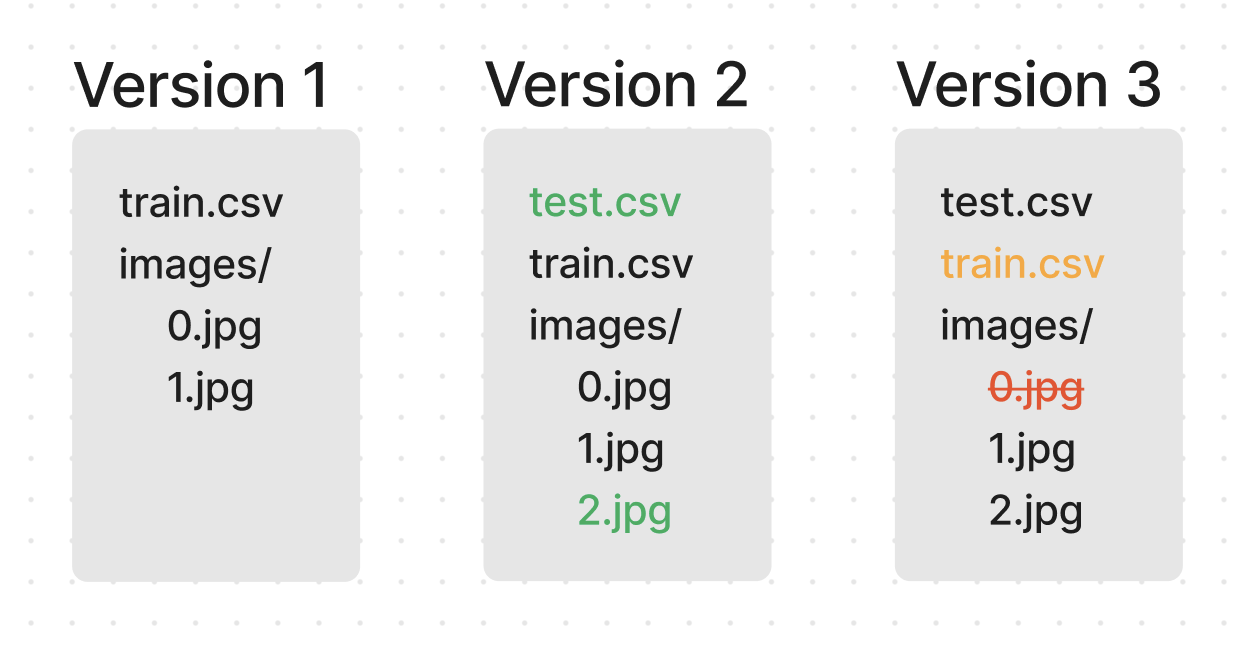

When we talk about data in Oxen, we usually talk about "Repositories". A Repository lives within your working directory of data in a hidden .oxen directory. You can think of a Repository as a series of snapshots of your data at any given point in time.

Each snapshot contains a "mini filesystem" representing all the files and folders in that snapshot. The each mini filesystem is represented by a commit, and is stored in the .oxen directory so that we can return to it at any point in time.

To see this in action let's instantiate a local oxen repository and see what it looks like.

$ oxen init

$ ls -trla

total 0

drwxr-xr-x 23 bessie staff 736 May 22 16:41 ../

drwxr-xr-x 3 bessie staff 96 May 22 16:41 ./

drwxr-xr-x 10 bessie staff 320 May 22 16:41 .oxen/

This magic .oxen directory is what will hold all the snapshots of your data. Think of it as a local database that lets you roll back your data to any point in time.

Content Addressable File System

How are the different versions stored on disk? Let's add and commit some files to the repository and see what happens.

$ echo "Hello" > hello.txt

$ echo "World" > world.txt

$ oxen add hello.txt world.txt

$ oxen commit -m "Add hello.txt and world.txt"

Each file that gets added and committed to oxen gets stored in a Content Addressable File System in the .oxen/versions directory. Oxen first computes a hash of the file, then stores the file in a sub directory that mirrors the hash. This means that the file can be retrieved by its hash at any time.

$ tree .oxen/versions

.oxen/versions

└── files

├── 18

│ └── 066113d946cfa640ffc8773c83f61b

│ └── data

└── a7

└── 666c8f5aaf946ca629d9d20c29aa6a

└── data

6 directories, 2 files

What's up with these funky hexadecimal directory names? Well each directory is a hash of the file. To see this in action, Oxen has a handy command to inspect information about an individual file.

oxen info -v world.txt

hash size data_type mime_type extension last_updated_commit_id

18066113d946cfa640ffc8773c83f61b 6 text text/plain txt 2c610ae8e424a4c8

oxen info prints out a tab separated list of the hash, size, data type, mime type, extension, and the last updated commit id of the file.

In this case, the hash for the world.txt file is 18066113d946cfa640ffc8773c83f61b. As for the directory structure above, you can see we split the hash and use the first two characters (18) of the hash as a prefix to the directory name. This is a common pattern in content addressable file systems to make sure you do not have too many sub-directories in a single directory.

Manually Inspect Older Versions

Currently the files in Oxen are uncompressed in the versions directory, so you can simply cat the file to see the contents.

$ cat .oxen/versions/files/a7/666c8f5aaf946ca629d9d20c29aa6a/data

Hello

Note: We have compression in our list of future improvements that could be made to the system, but the fact that we keep them uncompressed is a nice property of the system. It allows us to take advantage of the native file format of the files on disk with out additional compression / decompression steps.

Storing New Versions

Let's change the hello.txt file and commit it again.

$ echo "Hello, World!" > hello.txt

$ oxen add hello.txt

$ oxen commit -m "Update hello.txt"

Now look at the .oxen/versions directory. You will see that we have a new hashed directory for the file. This means that the file has been updated and a new snapshot has been created.

$ tree .oxen/versions

.oxen/versions

└── files

├── 18

│ └── 066113d946cfa640ffc8773c83f61b

│ └── data

├── a7

│ └── 666c8f5aaf946ca629d9d20c29aa6a

│ └── data

└── ce

└── 1931b6136c7ad3e2a42fb0521986ba

└── data

8 directories, 3 files

Let's look at each individual file in the versions dir.

$ cat .oxen/versions/files/a7/666c8f5aaf946ca629d9d20c29aa6a/data

Hello

$ cat .oxen/versions/files/18/066113d946cfa640ffc8773c83f61b/data

World

$ cat .oxen/versions/files/ce/1931b6136c7ad3e2a42fb0521986ba/data

Hello, World!

While this doesn't give you the full picture of how Oxen works, hopefully gives you a starting point into the Content Addressable File System that Oxen uses to store all versions of the files. We will get into the details of the commit databases and other data structures as we dive into more domains.

LocalRepository

Since all of the data for all of the versions is simply stored in a hidden subdirectory, the first object we introduce is the LocalRepository. This object simply represents the path to the repository so that we know where to look for subsequent objects.

src/lib/src/model/repository/local_repository.rs

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct LocalRepository { pub path: PathBuf, // Optional remotes to sync the data to remote_name: Option<String>, pub remotes: Vec<Remote>, } }

Whenever starting down a code path within the CLI the first thing we do is find where the .oxen directory is and instantiate our LocalRepository object.

There is a handy helper method to get a repo from the current dir. This recursively traverses up in the directory structure to find a .oxen directory and instantiates the LocalRepository object.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let repository = LocalRepository::from_current_dir()?; }

You may want to reference the code for the add command to see how instantiating a LocalRepository works in practice.

You will notice that not only does a LocalRepository have a path, but it also has a remote_name and remotes. These are read from .oxen/config.toml and tell inform Oxen where to sync the data to.

Remotes

A remote in the context of Oxen is simply a name and a url. The name is a human readable representation and the url is the actual location of the remote repository.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct Remote { pub name: String, pub url: String, } }

The remotes can be set through the oxen config command.

oxen config --set-remote origin http://localhost:3001/my-namespace/my-repo

If you look in the .oxen/config.toml file you will see the remotes listed there.

remote_name = "origin"

[[remotes]]

name = "origin"

url = "http://localhost:3001/my-namespace/my-repo"

You can have multiple remotes as well as a default remote specified by remote_name. The default remote is the remote that will be used when you run oxen push or oxen pull without specifying a remote.

RemoteRepository

On the other end of the LocalRepository is the RemoteRepository. This object represents the remote repository that the LocalRepository is connected to. It has the same url as the Remote object.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct RemoteRepository { pub namespace: String, pub name: String, pub remote: Remote, } }

All repositories that are stored on the oxen-server have a namespace and name. This helps us organize the repositories on disk, as well as in a way that is meaningful to the user.

In order to create a RemoteRepository we will first need to spin up an oxen-server instance. From your debug build you can do something like the following.

export SYNC_DIR=/path/to/sync/dir

./target/debug/oxen-server start

This will start a server on the default host 0.0.0.0 and port 3000. The environment variable SYNC_DIR tells the server where to write the data to on disk.

Then we can use the oxen create-remote command from the CLI.

oxen create-remote --name my-namespace/my-repo --host 0.0.0.0:3000 --scheme http

If you look in the SYNC_DIR you will see a directory structure that mirrors the namespace/repo-name of the repository you just created. There will be a .oxen directory with the remote repository created for you as well.

ls -trla /path/to/sync/dir/my-namespace/my-repo/.oxen

What's cool is that on disk the RemoteRepository is the same structure as the LocalRepository. This means that we can use the same code to manipulate the RemoteRepository on the server as we can the LocalRepository on the client.

If you didn't configure the remote earlier, you can do so now.

oxen config --set-remote origin http://0.0.0.0:3000/my-namespace/my-repo

Then simply push the data to the remote.

oxen push

This copies all the data from the local .oxen directory to the remote repository. Remember the versions directory from before? Let's see what it looks like on the remote.

$ cat /path/to/sync/dir/my-namespace/my-repo/.oxen/versions/files/ce/1931b6136c7ad3e2a42fb0521986ba/data

Hello, World!

There we go! Data is in tact on the remote server. This is the beauty of Oxen. There are not too many fancy bells and whistles when you look under the hood. Just a content addressable file system with a library that is shared between the client and server.

Next up we will look at Commits. These objects represent the group of files that were are in a single snapshot, and we will learn how Oxen knows which versions were added, removed, changed in the repository and when.